Download the blog post as a PDF>>

This post is part of the report The Washington Region’s Economy in 2017 and Outlook for 2018 and Beyond.

Download the Full Report>>

With the national economy’s projected strong performance setting the framework, the Washington region is projected to achieve stronger economic growth in 2018 than it did in 2017 but job growth will slow, for many of the reason enumerated earlier (normal for this stage of the business cycle, shortage of qualified labor, rising wage rates, increased productivity). Beyond the national economy’s expected strong performance, the Washington region’s mix of new jobs and the economy’s ability to pivot away from its federal dependence will determine its economic performance in 2018. And, federal fiscal policy will continue to have an impact on this year’s performance and beyond.

The burden that the Washington region’s economy is carrying in 2018 and beyond is the likelihood of flat or declining federal spending. If this proves to be the case, then the region’s economic growth will fully depend on the growth of its non-federally dependent export-based sectors and local-serving sectors that also serve non-local markets. If the Washington region’s economy is to outperform this baseline forecast, it will require federal spending to increase thereby generating additional growth beyond that which can be generated in the absence of the growth of federal spending. This added federal spending could consist of growth in federal jobs and payroll or increases in federal procurement outlays to the benefit of local contractors or both.

Job Growth Forecast for the Region’s Sub-State Areas

The job growth forecasts for 2018 and the following four years are presented in Table 1. After generating substantial job gains in each of the previous three years (2015, 2016, and 2017) and exceeding the long-term annual average by more than 20,000 jobs for each of those years, the region’s job growth is projected to moderate in 2018 and 2019 and then fall below the historic long-term average annual gain in 2020.

In the near-term, the job growth projections for 2018 and 2019 remain well above the long-term average for the Washington region; however these gains are not evenly spread throughout the sub-state areas of the region. As the economy begins to moderate in 2019, after peaking in 2018 and with the aging of the business cycle, the sectoral structure of the separate sub-state portions of the region will increasingly shape their own economic futures.

The District of Columbia is the most dependent (directly and indirectly) among the three sub-state areas on the federal government for its economic vitality and its economy is the most specialized. Among the District’s principal “growth” sectors, the federal government is projected to continue contracting its job base each year through 2022 with an accumulated loss of 5,200 jobs between 2018 and 2022. The education and health services sector registered a strong gain in 2017 and is expected to add 2,100 additional jobs in 2018. However, after 2018 this sector is not projected to increase further and is projected to experience small job losses in 2020 and 2021. Leisure and hospitality services added an estimated 5,000 jobs in 2017, for a 6.7 percent gain, reflecting the opening of the Wharf and several new hotels as well as the benefits of a Presidential Inauguration year. Its growth is projected to moderate in 2019 and then will remain relatively steady and positive over the remainder of the forecast period.

The District’s largest private sector, second in size only to the federal government among all sectors, is professional and business services. This sector is projected continue its strong pattern of growth in 2018 and increase 2.2 percent, slightly exceeding its 2017 rate of 2.1 percent. Gains in this sector accelerate in 2019 (2.7%) and then moderate slightly maintaining a growth rate near 2.3 percent for the 2020-2022 period. The challenge for the District of Columbia’s economy is that its growth depends almost entirely on one sector, professional and business services, which is projected to account for from 65.0 to 100.0 percent of its net job gain in each of the next five years. The continuing contraction of so many of its other sectors is making the District’s economy overly dependent on fewer sectors at a time when its largest sector—the federal government—is projected to decline. As a consequence, the District’s job growth will experience a greater slowdown than the region’s two suburban sub-state areas over the coming five years.

Suburban Maryland experienced what might appear as a breakout year for job growth in 2017. But this unusually strong performance is largely explained by one-time expansions in two sectors that have not positioned the sub-region for a repetition of this magnitude of job growth in 2018 and beyond. These one-time expansions occurred in Prince George’s County—the opening of the MGM Casino and the expansion of state and local government agencies; these two expansions respectively swelled the county’s leisure and hospitality and state and local government job totals that together accounted for 12,200 new jobs in 2017, based on the preliminary release. Because of a likely downward revision to the state and local government jobs, the revised total will be somewhat smaller, at around 7,000-8,000. Combined, these two sectors are expected to add 5,100 new jobs in 2018 and only 1,500 new jobs in 2019.

After this strong showing in 2017, job growth in Suburban Maryland economy is projected to slowdown in 2018. Its challenge is that the sub-state area’s economy is specialized in the federal government’s non-defense agencies and the state and local government sector is accounting for a growing percentage of its job base. Additionally, Suburban Maryland’s private sector economy depends too heavily on local-serving businesses. With federal spending for domestic programs projected to slow and possibly decline, and local-serving businesses projected to grow more slowly after 2018, Suburban Maryland’s economy is not well positioned for faster growth going forward.

The performance of Northern Virginia’s economy remains closely tied to federal procurement spending as seen in the continuing strong performance of its professional and business services sector; this is the sector in which most of the federal contractors are located. Projections show this sector in Northern Virginia accounting for more than one-half of the Washington region’s job growth in this sector and, within Northern Virginia, this sector’s gain is projected to account for more than one-half of the sub-region’s total job growth each year over the forecast period. Education and health services are projected to experience a strong gain in 2018 but then its growth is expected to moderate but still grow each year in the out years of the forecast. Leisure and hospitality services are also projected to continue growing in the out years after a relatively weak growth forecasted for 2018. Two other important sources of Northern Virginia’s job growth in 2018 will be financial services and construction. Beyond these, Northern Virginia’s other sectors are projected to experience marginal gains or losses over the forecast period and not contribute to the sub-state area’s overall growth rate.

None of the Washington region’s sub-state areas is showing signs of diversification across their private sectors. The District of Columbia’s private sector economy is narrowly concentrated on professional and business services, education and health services and leisure and hospitality services and slower job growth is projected for the latter two sectors making the District’s economy even less diversified in 2022 than it is today. The Suburban Maryland economy is specialized in government (federal, state and local), leisure and hospitality services and educational and health services with local-serving businesses being a large component of these non-government sectors. The professional and business services sector is a relatively small part of Suburban Maryland’s economic base compared to the District of Columbia and Northern Virginia. This mix of sectors is not favorable to job growth or to the growth of higher-value added jobs to offset the slow erosion of federal jobs in Suburban Maryland over the next five years.

Northern Virginia’s economy has a strong professional and business services sector that will drive its future growth. This sector is complemented by broad-based strength in education and health services, leisure and hospitality services and growth in construction and financial services although these latter two sectors will experience slower growth after 2019.

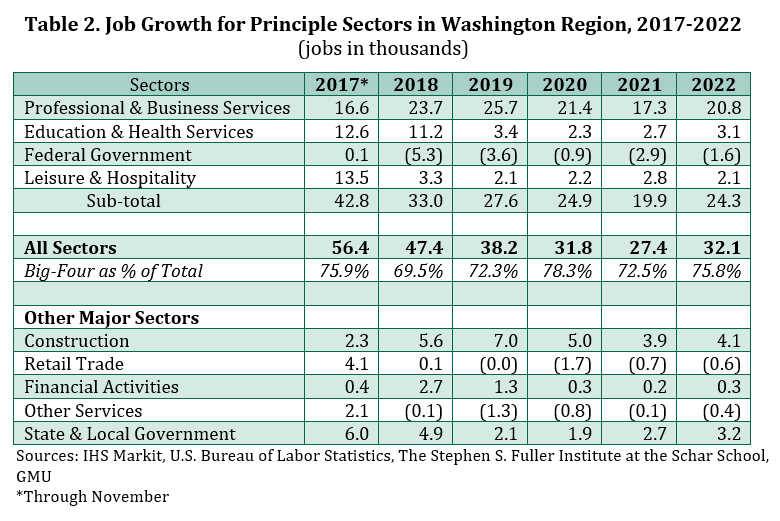

Job Growth Forecast For Region’s Principal Sectors

The sum of these sub-state areas describes the regional economy’s job growth patterns for the next five years, as summarized in Table 2. The patterns are clear: the professional and business services sector will become more important to the region’s economic health as the other large sectors—federal government, educational and health services, and leisure and hospitality services—either decline or experience slower growth. Of the other larger sectors, construction and state and local government will continue to grow. Financial services will experience little or no job growth after 2019 while retail trade and the other services sector will both expected to be losing jobs by 2020.

The job forecasts for 2018 and 2019 are for above-trend gains but the foundations for future economic growth will have become more narrowly specialized in the private sector. In the absence of increased federal spending in the region’s economy, the region’s private sector will not be able to sustain the higher growth rates achieved in 2018 and 2019 into the out years.