By Stephen S. Fuller, Ph.D.

Download as a PDF

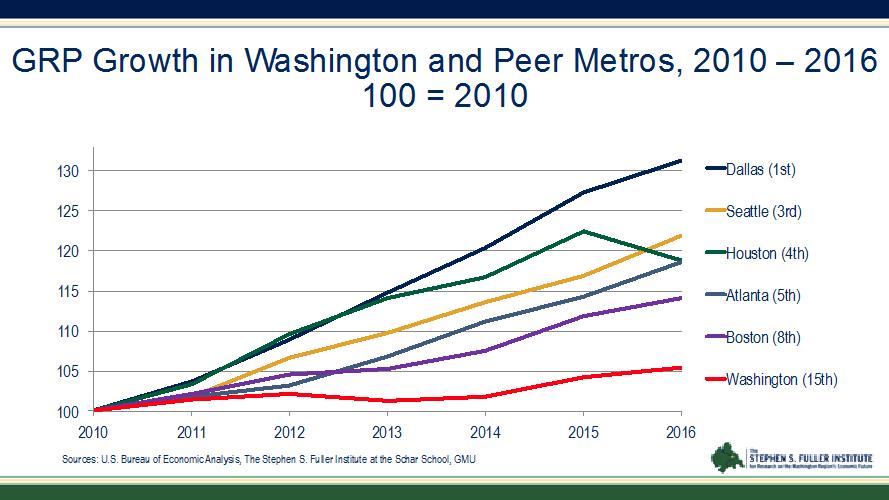

The performance of the Washington region’s economy has been lagging its peer metropolitan areas since 2010 and a recent report from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis shows the Washington region’s economy has preformed worse than had been previously reported. The principal reason for the Washington region’s poor economic performance has been shown to be its overdependence on federal spending to drive its economic growth in a period of reduced federal employment and procurement outlays.

The Washington Region’s Job Growth Since 2010 Has Favored Lower-Value Added, Local-Serving Sectors

Continuous growth in federal spending in the Washington region during the 1980-2010 period propelled the Washington region’s economy at rates exceeding the growth rates of all but one of the other fourteen largest metropolitan areas (the Washington region’s economy currently ranks 5th in size) in the U.S. Based on job growth and mix, it is likely that only the Atlanta region’s economy grew faster than the Washington region over the 1980-2010 period while the Dallas region’s growth rate was close.

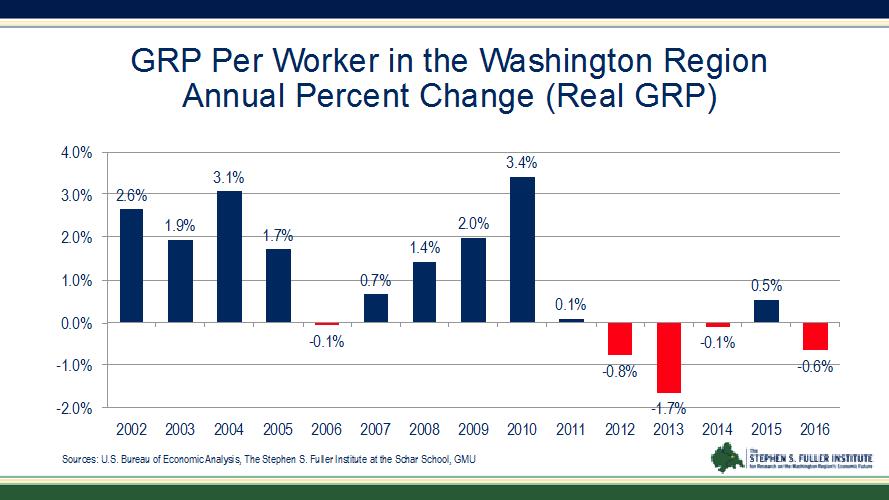

Since 2010, with reductions in federal employment and procurement spending and in the absence of compensating growth in export-based, high-value added, non-federally dependent businesses, the job growth that has occurred has increasingly been concentrated in lower-value added and local-serving businesses. As a result of this altered pattern of economic growth, the annual average value-added to the economy per worker in the Washington region has declined from a positive average annual rate (1.65%) during the six years preceding the Great Recession to a negative average annual rate (- 0.43%) over the six years since the Great Recession.

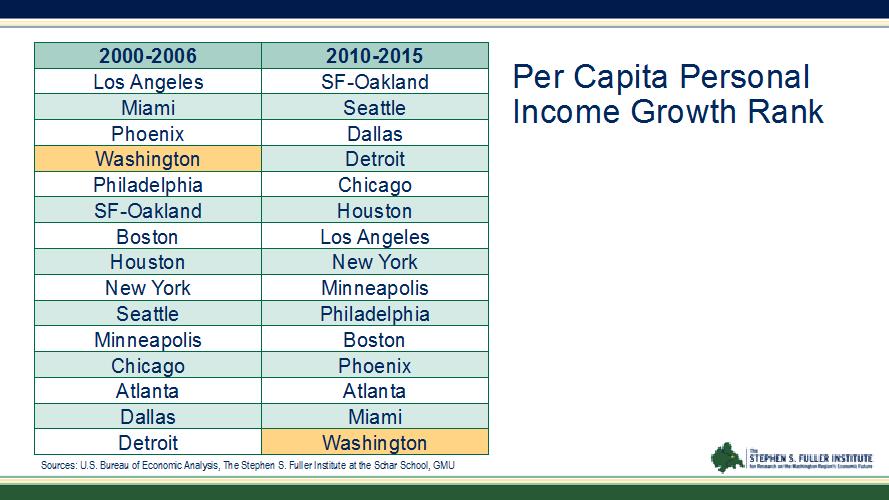

The consequences of this shift in the Washington region’s economic structure and the dilution of the economic value of its employment base are evident in the region’s slower growth in per capita personal income. During the 2000-2006 period, the Washington region’s per capita personal income growth rate ranked fourth among the largest 15 metropolitan areas but fell to 15th place, the slowest growth rate, during the 2010-2015 period.

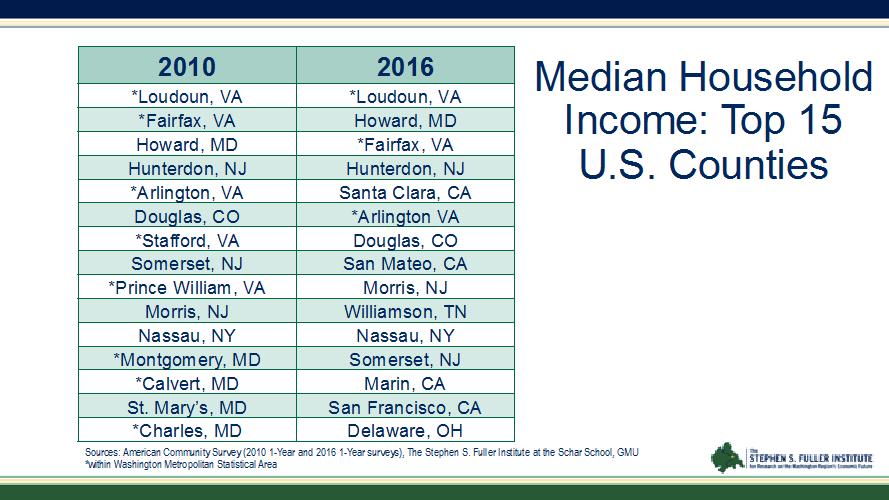

Still, the Washington region had the highest median household income among the nation’s fifteen largest metropolitan areas in both 2006 and 2015 but this top position may be threatened by slower household income growth in 2016, as recently reported at the county level. This slowing in the region’s economic growth is seen in data released by the U.S. Census Bureau in September 2017 in which average household income for the nation’s local jurisdictions was reported and counties ranked by value. As recently as 2010, 8 of the top 15 counties, ranked by their median value of household income, were within the Washington region (as defined by the U.S. Census). However, in 2016, the Washington region only had 3 counties on this list.

While Loudoun County retained its number one ranking as having the highest, median household income, Fairfax County slipped from second to third place and Arlington slipped from fifth to sixth place. In 2016, the median household incomes in Stafford County, Prince William County, Montgomery County, Calvert County, and Charles County no longer placed them among the top fifteen counties nationally.

Of the two Maryland counties contiguous to the Washington metropolitan area and connected to the region’s economy—Howard and St. Mary’s Counties—that were on the list of the top 15 highest median household incomes in 2010, only Howard County remained in 2016; and it moved up to second place. Howard County’s continuing strong household income growth may be explained by its stronger economic connection to the Baltimore metropolitan economy than with the Washington region’s economy that has enabled it to better compensate for slower growth in the Washington region’s economy; that is, is has been able to benefit from the diversification offered by the combined metropolitan areas’ economies where workers residing within the Washington metropolitan area have been disadvantaged by the Washington region’s inability to diversify away from its federal dependence.

The Washington Region’s Economy Has Been Slow To Diversify

A regional strategy for diversifying the Washington region’s economy to reduce its dependency on federal spending to drive its economic growth and its resultant vulnerability to shifts in federal fiscal policy was formulated in The Roadmap for the Washington Region’s Economic Future that was released in January 2016 (see sfullerinstitute.gmu.edu). The Roadmap identified seven export-based, high-value added, non-federally dependent advanced industrial clusters and that had high growth potential for which the Washington region appeared to have a competitive advantage that offered an alternative growth path to being a “company town.” While performance of these advanced industrial clusters in the Washington region’s economy is not tied directly to federal spending, the national capital functions headquartered in the Washington region, the quality of the region’s workforce, and the quality-of-living in the region provide a clear competitive advantage to businesses encompassing these clusters, whether they be profitmaking or not-for-profit organizations.

Research reported in the Roadmap showed these clusters had significant growth potential within the national economy and that they already had disproportional concentrations of workers in the Washington economy; that is, they each constituted a higher percentage workers in the Washington region’s economy than in the national economy confirming the region’s competition position for their respective future growth. The research also showed that the growth of these advanced industrial clusters would generate disproportional growth in local-serving sectors making them good candidates to compensate for future declines in the federal sector in support of the region’s future economic growth.

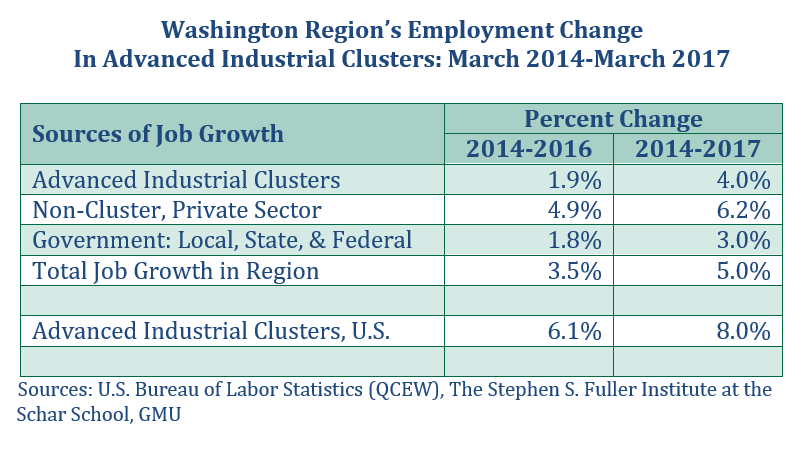

In February 2017, the Fuller Institute reported on the performance of these advanced industrial sectors for the first two years since the Sequester in 2013 drove the region’s economic growth negative, losing 0.8 percent that year, and suppressed its growth in 2014 when the economy eked out a 0.5 percent gain. For the two-year period March 2014 to March 2016, the region’s advanced industrial clusters were found to have underperformed their counterpart clusters at the national level and also underperformed the Washington region’s non-export based, largely local-serving sectors.

This report was not encouraging and the region’s economic indicators for 2016 reflected this weak performance. Other than for strong job growth, which was dominated by lower-value added jobs, the region’s other metrics by which the region’s economic performance could be measured (e.g., GRP increased 1.1%, value added per worker decreased 0.6%, per capita personal income increased the slowest of the 15 largest metropolitan areas) confirmed the region’s lagging performance.

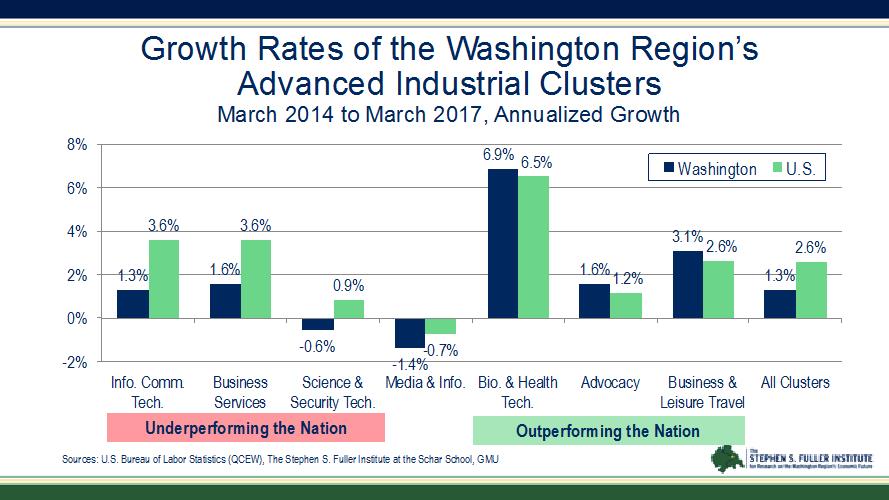

Recently released data for the March 2016-March 2017 period for the region’s advanced industrial clusters show stronger growth compared to the first two years. The cluster-based job growth in the region out-performed the non-cluster job growth but still fell behind their respective clusters’ job gains at the national level. Still, over the full three-year period, the Washington region’s non-federally dependent clusters are lagging locally and nationally. In aggregate, the Washington region’s seven advanced industrial clusters have experience 1.3 percent average annual job growth over three years while at the national level these same clusters averaged 2.6 percent annual job increase.

While the seven clusters are underperforming in aggregate, three of the region’s clusters have out-performed their respective cluster nationally—biological & health technology services, advocacy services, and business and leisure travel services. However, these three clusters accounted for less than one-third (31.5%) of all of the region’s jobs in its seven advanced industrial clusters in 2014.

This was an improvement from their 2014-2016 performance. Biological and health technology services, the smallest of the region’s seven clusters, registered a strong performance during the 2014-2016 period (5.1% annually) while business and leisure travel services (1.0% annually) was positive but only average while the advocacy cluster’s 1.4 percent annual average gain fell below its forecasted potential.

That these two, previously slower-growing clusters reported stronger gains in the March 2016-March 2017 period underscores the importance of being located in the Nation’s Capital. Clearly, the Presidential election cycle is likely to have bolstered the advocacy cluster, especially with a change of Administrations. The inauguration activities, complemented by opposition demonstrations, might be credited for the enhanced performance of the business and leisure travel services cluster. The opening of the MGM National Harbor Casino in December 2016 and the opening of several other new hotels in the region, including the Trump International Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, also boosted this cluster.

The four clusters that continued to underperform their respective clusters nationally accounted for 68.5 percent of all of the region’s cluster-based jobs in 2014. That they continued to lag behind their respected national clusters should be a concern to local business leaders and elected officials. The continuing weak performance of these clusters, clusters shown to have substantial growth potential at the national level and for which the Washington region has a competitive advantage, points to the region’s clusters not successfully penetrating national and global markets either for failing to try or for actually not being competitive.

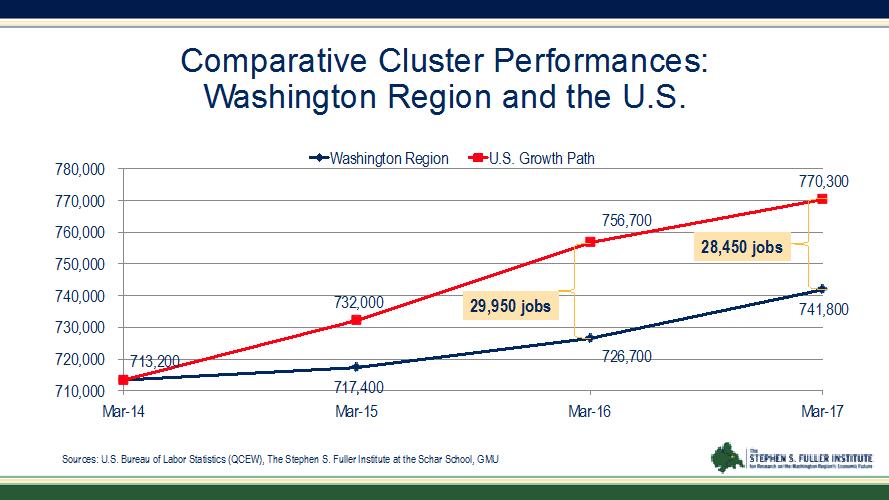

At the beginning of the analysis period, March 2014, the region’s advanced industrial clusters had 713,000 jobs, accounting for 31.5 percent of the all private sector jobs in the Washington region. By March 2017, these clusters accounted for 743,693 jobs or 31.1 percent of the region’s private sector job base. With non-cluster private sector jobs growing at a 6.2 percent three-year rate and cluster-based jobs growing at 4.0 percent for this same period, it is clear that these non-federally dependent, export-based, high-value jobs—the jobs that could compensate for the loss of federal spending in support of the Washington region’s economy—have not achieved their performed up to expectation.

Slower Economic Growth Has Long-Term Consequences

The consequences of the region’s underperformance of its advanced industrial clusters are shown below. Had the Washington region’s advanced industrial clusters grown at their respective national growth rates over the 2014-2025 period, the region’s employment base would have gained 28,450 more export-based, high-value added, non-federally dependent jobs than if it continues on its current lower trajectory. If this performance continues to 2025, the cost to the region’s economy will total $169 billion in unrealized economic growth, the difference between averaging 2.8 percent and 1.9 percent average annual growth rate between 2014 and 2025, the trajectory on which the region’s economy is current tracking.

The Washington Region’s Economy Remains Vulnerable To Changes in Federal Fiscal Policy

The Washington region’s economy is not growing its export-based, high-value added, non-federally dependent business base sufficiently fast to counter-balance the contraction it has experienced in its historically dominant federal sector. In fact, the region’s advanced industrial clusters, businesses that have the potential to compensate for this loss of federal spending, are under-performing their respective clusters in the national economy.

The result is that the federal sector’s share of the region’s economy has declined from 39.8 percent in 2010 to its present estimated share of 29.9 percent in 2017 with the difference being made up by a combination of expansion of local-serving sectors, up from 34.8 percent to 38.0 percent, non-local serving (export) sectors, up from 12.0 to 15.2 percent, international businesses, up from 3.5 to 3.9 percent, education and health services, up from 4.5 to 7.0 percent (these are predominantly local serving), and leisure and hospitality services, up from 2.1 to 2.6 percent largely on the strength of increased food and beverage services serving local demand.

Until the region’s export-based, high-value added, non-federally dependent businesses (these can be federally related but not dependent on direct funding) accelerate their growth to rates equal to or greater than their respective nationally averages, as they are in the region’s peer economies, the economic performance gap between the Washington region and its peers will continue to widen. This pattern has occurred in history—following the end of the World Wars I and II, the Vietnam War, and since 2010 due to the federal spending cuts initiated under the Budget Control Act of 2011.

This pattern of declining federal spending that started in 2010 could continue to the end of this decade given the policy directions of the current Administration. Without an offset in growth in the non-federally dependent clusters having an economic profile similar to the federal sector (export-based and high-value added) to compensate for this lost spending, the Washington region can expect and should plan for slower future growth than what it had been accustom to prior to 2010.