From Bloomberg:

Beyond the boom of younger workers flooding in, Washington is grappling with longer-term economic challenges

The Washington, D.C. economy is preparing for the day when younger workers break up with it.

The fading of a millennial-infused population boom in the nation’s capital that carried through the Obama years, combined with Trump’s efforts to slash the federal workforce, are but two factors that have the local economy locked in a painful transition from skyrocketing growth reliant largely on its federal patron to a more diversified and self-sustaining market.

The 68-square-mile city could be in for some more growing pains as the Trump administration has directed agencies, effective Thursday, to hire only in line with levels proposed in the president’s “skinny budget” submitted last month.

Meanwhile, businesses, economists and policy makers are grappling with bigger challenges for D.C.:

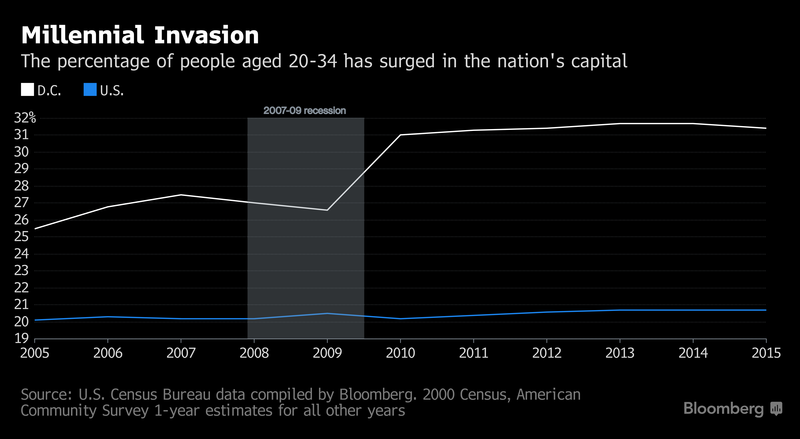

- Population and the millennial boom

From 1990 to 2000, D.C. was alone against the 50 states and Puerto Rico to see a decline in population, of 5.7 percent. In the decade following, Michigan earned that dubious title while Washington made up ground with a 5.2 percent increase. And in the more than half-decade since, the city enjoyed a 12.6 percent boom while the country saw population growth of around 4.5 percent.

The outlook depends on millennials, who flocked to the city as a haven for jobs after the last financial crash. While the city remains attractive for its job and income prospects relative to other urban hot spots, expensive childcare could prompt outflows of those younger residents, according to a March report on millennials in D.C. by American University and commissioned by Kaiser Permanente.

For Neil Albert, president and executive director of the DowntownDC Business Improvement District, the city’s still doing just fine in this respect.

“We have strong assumptions of population growth, and the population continues to grow at a pretty healthy clip,” at around 800-900 residents a month, he said.

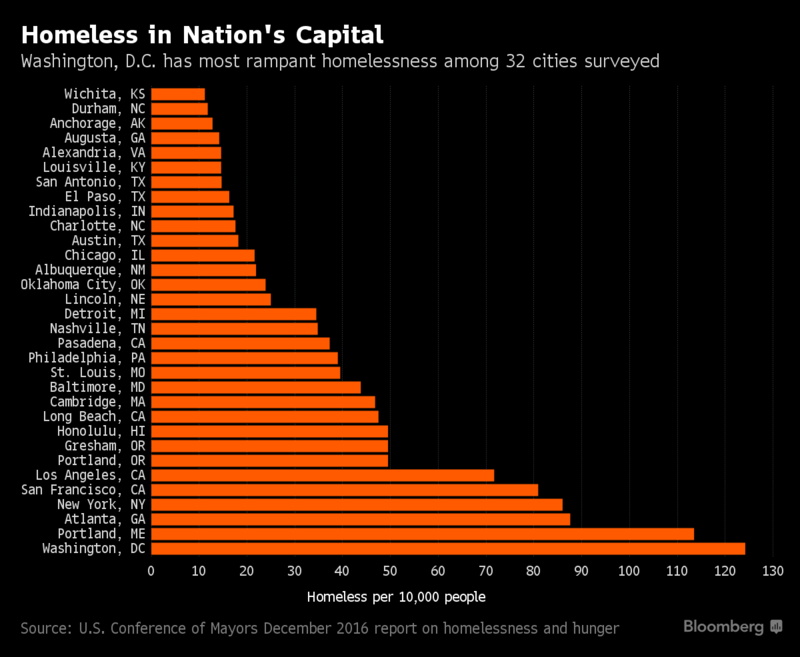

- Homelessness and housing prices

Beneath the lush opportunities for young people and other middle- and higher-income job holders in the city is a still-plentiful army of homelessness, helping to show why the city remains challenged by rampant inequality. Washington ranked worst in homelessness among 32 cities whose mayors are members of the U.S. Conference of Mayors Task Force on Hunger and Homelessness, according to the group’s December report.

For homeless people to climb into an earnings bracket that will allow them to afford their own housing, the stock of low-income homes will have to increase.

“The elephant in the room is there’s no place for people to live — there’s not low-cost opportunities for people to live when they are trying to come out of homelessness,” said David Whitehead, housing program organizer at Greater Greater Washington, an advocacy group and community blog.

Rob Wohl, tenant organizer at the Latino Economic Development Center, said the city is putting forth “unprecedented” spending on affordable housing development, but is “still losing more low-cost housing than we’re building.”

An index of housing prices in Washington has increased nearly 30 percent to 217.12 since the post-recession trough in April 2009, exceeding the 26 percent rise nationally, according to S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller data. Renting is also incredibly pricey, with the median monthly bill for a two-bedroom apartment listed at $3,050, the fourth-most expensive of the 100 largest cities in the country, Apartment List data show.

The soaring housing bills have pushed many longtime Washington residents out to the suburbs, though they also threaten the viability of city living for the middle class.

“I’d be worried that not investing enough in affordable housing could damage the ability to have a diverse economy and draw in the kinds of young people who could stay for the long term,” said Ed Lazere, executive director of the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute.

- Federal share of jobs

For decades, the economic engine of the city has relied on what Yesim Taylor calls “Fortune One,” or the government, rather than any Fortune 500 firm. Taylor, the founder and director of the D.C. Policy Center and former director of fiscal and legislative analysis for the city’s government, laments that the region isn’t diversified enough and has failed to attract high-value companies to house themselves alongside the federal government.

While the government’s share of jobs in the region has ebbed, it’s still quite high, according to Jeannette Chapman, deputy director of the Fuller Institute at George Mason University. In the immediate two years following sequestration, ending in March 2016, government jobs increased just 1.8 percent while all jobs in the Washington metropolitan area grew 3.5 percent, according to tallies by the Institute, which studies the city’s economy.

Chapman said she’s also concerned that most of the newly created jobs have been low-skilled, “resident-serving” jobs such as retail that simply respond to population growth and don’t build the economy for the longer term. Advanced industry jobs grew just 1.9 percent during that two-year period.

Even as the tech industry in the region has been “really, really, really, really good at delivering innovation in the services model,” the sector hasn’t yet adjusted as it should to a more product-oriented approach, said Jonathan Aberman, professor of entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business.

“What you have is a very clear picture of an innovation community that is configured completely wrong to deal with the coming tsunami of government spending changes on technology,” said Aberman.

- Restaurant glut?

One part of that shift in the mix of D.C. jobs has been a boost to the restaurant industry, in a city once mocked for its lack of foodie bona fides.

“We’ve developed this whole restaurant industry, which has really exploded in the last several years,” said Tony Tomelden, owner of The Pug restaurant on H Street NE. “This city has less and less to do with the government.”

While Tomelden is cautiously optimistic those industry gains can continue, others are less confident.

Up on U Street NW, Kamal Ali, who helps manage Ben’s Chili Bowl and is son of the late founder Ben Ali, is bracing for some neighborhood businesses to lose out as the explosive growth around him pauses.

“Right now there are perhaps too many restaurants, in particular, and could be other retailers,” said Ali. “I do see some will turn over due to the lack of viable support for them. A lot will do really well, but there will be some who fall by the wayside.”

Chapman, too, sees Peak Restaurant in the past, at least for now.

“The restaurant growth in the District — a lot of that was playing catch-up as the District was considered to be a less-than-enviable food environment,” said Chapman. “Since the District’s population growth, which has been good, is starting to pull down a little bit, I think the restaurant growth will start to pull down.”

- Surplus in city coffers

With a surplus of about $1.9 billion, the city is hardly scraping at the bottom of the piggy bank. Spending is restrained in part by the city’s governance structure — “taxation without representation” also has meant that Congress effectively retains veto power over City Council decisions.

At the same time, whether to dial up or back on taxes and regulation — and whether those moves would threaten or boost business — remains a heated debate.

“Right now there seems to be this trend that we’re so labor-friendly that it’s going to choke out some businesses as well because the margins aren’t so great,” said Ali. “It’s not that people don’t want to do the best by their employees but there are some things where I’ve seen we’re going to be the second in the whole country to do something. It’s like, maybe we can work the kinks out, maybe we can be the 15th to do it.”

Ali noted that the city was undertaking ambitious plans to revamp paid leave, transportation allowances, and predictive scheduling policies, while not always taking into account how the implementation can be counterproductive both for workers and businesses — as with scheduling that binds both sides to certain hours, leaving little room for last-minute flexibility.

The District recently approved the nation’s most generous paid family leave law, allowing up to 16 paid weeks for most privately employed workers. But the D.C. Chamber of Commerce, among others, has decried the legislation as too onerous for business.

In perspective

However monumental the economic challenges, Virginia Ali, co-founder of Ben’s Chili Bowl, takes solace that her business has thrived through even tougher times since its start in 1958: the neighborhood riots in the 1960s in response to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, and construction of the U Street metro in the early 1990s that forced closure of most businesses on the block and sent the remaining three (including Ben’s) home at dusk since there were no street lights.

“From 1968 to the late ’80s, it was hard here — this area was very hard, very, very hard,” she said in a February interview. “Here we’ve got tourists all the time — cherry blossoms, the monuments, Congress. We’ve got everything here. We are a city of tourists, and now I think we’ll see more and more of them. We have a new administration but I don’t know anything about that and where it’s going — that’s a wait-and-see thing. That’s all that is.”